Chant Comment

GREGORIAN CHANT : A WAY OF PRAYER

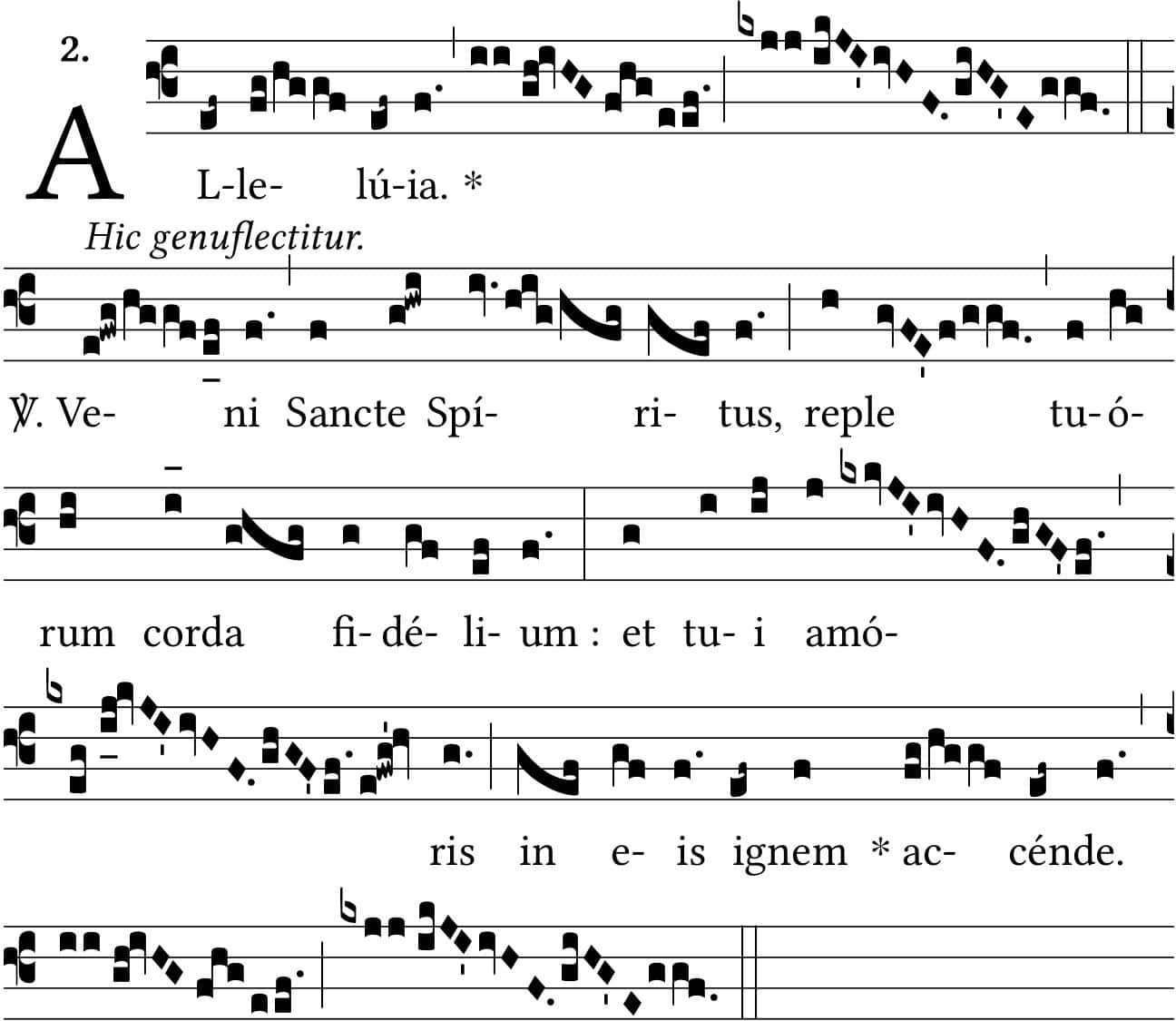

A commentary on the Alleluia for Pentecost

based on the “Scala Claustrorum”, or “Ladder of Monks”.

There exists a little 12th cent. treatise called The Ladder of Monks at present attributed to Guigo II, ninth prior of the Great Charter House (1173-11800. It is written in the form of a letter to a friend, and although very short and characterized by great simplicity and freshness of style, it has become a classic of monastic literature on account of the abundant and sound advice which it offers on the practice of prayer. Its advice is summarized in four steps which are to be climbed as a ladder, and which it describes as lectio-meditatio-oratio-contemplatio.

LECTIO – READING

MEDITATIO – PONDERING (or meditating)

ORATIO – PRAYING

CONTEMPLATIO – CONTEMPLATING

In fact, with all the originality of its presentation, Guigo’s work summarizes centuries of Christian mystical wisdom, a tradition based on Scripture, and nurtured in patristic thought and monastic practice. Through Guigo, we hear again the voice of Jerome, Augustine, Cassian, Anselm, Bernard and all those unnamed monks and nuns who found in Scripture daily bread for their souls, a meeting place with Christ and a channel for the action of the Holy Spirit.

It could be said that our Gregorian chant repertoire represents an extensive and contemporary record of that same process of lectio – meditatio – oratio – contemplatio described by Guigo in his “Ladder”. It is no coincidence that the repertoire grew precisely during those same centuries of patristic thought and monastic expansion, reaching its full flowering in the 12th century when Guigo was writing his short treatise. For those reasons, that Gregorian repertoire has been described as a “musical patrology ” (Canon Jean Jeanneteau, 1908-1992), for it represents, albeit in the language of music, a rich commentary on the revealed word of God, and is a fruit of that patristic tradition already mentioned. Gregorian chant, as Jeanneteau pointed out, was not composed for Scripture, but grew out of Scripture; similarly, it was not composed for prayer – it grew out of prayer.

I shall use as an example to demonstrate my point the Alleluia “Veni Sancte Spiritus” *of Pentecost; through it, I shall attempt to show some of the ways in which Gregorian chant manifests the process of lectio – meditatio – oratio – contemplatio as traced out in The Ladder of Monks.

* The Alleluia “Veni Sancte Spiritus” is found on three of our cassettes: Adorate Deum, Cantus Ecclesiæ and Spiritus Domini.

LECTIO “Reading comes first as the foundation” (Ladder, 10). The vast bulk of the body of Gregorian chant takes its text or inspiration directly from Scripture. The Alleluia “Veni Sancte Spiritus” is in fact one of the rare texts found in the Gradual (i.e. the collection of chants for Mass) which are not direct Scriptural quotations. It is, however, laden with Scriptural allusions, in particular Lk 11:13 (“If you then who are evil know how to give good things to your children, how much more will the heavenly Father give the Holy Spirit to those who ask him.”), Jn 14:15-17 (“If you love me you will keep my commandments. And I will pray the Father, and he will give you another Counselor, to be with you forever, even the Spirit of truth.”), Acts 2:3 (“And there appeared to them tongues as of fire, distributed and resting on each one of them. and they were all filled with the Holy Spirit.”), and Rom 5:5 (“God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit which has been given to us.”). It is important to realize that for the christians of the first millenium and beyond, Scripture was the staple diet of the spiritual life. It was the air they breathed, the medium in which they thought; above all it was the source and expression of their faith and prayer. Out of the hours of reading and recitation of these inspired texts emerged the tradition of Christian “cantillation” i.e. of sung Scripture reading, especially psalmody. This is the basis of the Gregorian repertoire even in its most evolved form. It is both proclamation and interiorization of the sacred text, for through proclamation the word dwells within us and resounds in the inner consciousness of both hearer and singer: “To listen pertains in a certain sense to reading.”(Ladder, 11). That this emphasis on hearing the sacred words remained the aim even in the most elaborate stages of Gregorian composition can be deduced from such clues as the proliferation of liquescent signs (manuscript signs to attract the singer’s attention to requirements of good diction); in our Alleluia there are 6 of these liquescent signs (not all printed in the commonly used “Vatican edition”). Another clue is found in the very structure of the melodies, which consistently reflects the importance of that basic “recitation note” of the original cantillation. The main words or phrases constantly return to this note as to a firm foundation, after the characteristic upward sweeps of the melody, as though to remind us that prayer, however elevated, must always return to that firm foundation of our faith, the revealed word of God. Our example demonstrates this very well, as there is a constant attraction back to that original recitation note – in this case Re – and some passages like in eis ignem accende are very close to a monotone recitation.

MEDITATIO “Seek by reading and you will find by meditation…Not content to remain on the surface or cling to appearances, meditation searches deeper, it penetrates underneath and ponders each word” (Ladder, 2 & 3). We have a reflection of that process in the passage from Gregorian psalmody to original compositions such as the antiphons of Office and the proper Mass chants. Psalmody manifests, in its austere repetitiveness and regular pauses, a voluntary poverty of form which frees the mind and the heart from distractions. Out of it arises meditation which centres on the inner meaning, or, in the language of Guigo, breaks open the shell in order to chew the kernel, digs down in order to discover the treasure (Ladder, 2 & 10). This results in a new creativity. As hitherto unseen depths of meaning emerge out of a text, it assumes new life and flowers into an original composition. This may involve the free adaptation of a Scripture text: our Alleluia is an outstanding example of that process, as already shown (see “lectio”). Such new compositions also acquire key positions within the liturgy, from where they can throw light onto their surrounding context. In this way, whether short and simple, like a Vespers antiphon, or longer and more evolved, like the Mass chants, they can reveal insights into the meaning of the Scripture text with a precision and profundity that can sometimes be startling. In the case of our Alleluia, the composer has seized on various New Testament texts connected with the themes of the Holy Spirit, the gift of love and the image of fire, blended them into a whole which he linked to the feast of Pentecost. Moreover, he has placed his composition just before the reading of the Gospel at Mass; in this way he has connected the coming of the Holy Spirit with the reading of the Gospel and with the Incarnation itself. All of these techniques – the combination of disparate texts within a single composition, or even the free adaptation of a Scripture text, the setting into musical relief of certain key words (see for example, the treatment of amoris in our case), and the situating of the composition within a particular liturgical context – serve as pointers to the new depths of meaning which the composer has extracted from the sacred text through “breaking its shell” in prolonged meditation.

ORATIO “Prayer is the devout turning of the heart to God…the entreaty of desire” (Ladder, 1 & 2). The new composition now develops a melodic dynamism of their own, the dynamism of desire which Guigo relates to prayer (Ladder, 10). It is expressed in the constant upward sweep of the Gregorian melody which, taking its impulse from the original recitation note, always returns to it for rest. Our Alleluia verse is a perfect example of this, with the insistent rising and falling of its melody. Here we find “prayer which, raising itself with all its strength to God, begs for this desirable treasure, the sweetness of contemplation” (Ladder, 10)?

“It is,” says Guigo, “as if reading put the solid food into the mouth, meditation broke and masticated it, and prayer acquired the flavour, of which contemplation is the very sweetness” (Ladder, 2). That “flavour” spoken of by Guigo corresponds to what in Gregorian chant we call “modality”. Modality is a musical “climate” created by the interrelationship of the structural notes upon which the melody is built. The musical mode has a capacity to express the “mode” in which we relate to a person or situation. In our example, it is the Re and the Fa which ceaselessly call to each other, in an interplay which creates the climate of interiority and reverence that is so characteristic of the 2nd mode. Other modes create different climates. But all the modes have in common the characteristic of creating or expressing relationship. Through them the words of Scripture pass from the stage of meditation to that of prayer i.e. from a monologue to a dialogue with God.

CONTEMPLATIO “When contemplation comes, it rewards the toil of the first three…Contemplation is that raising up whereby the mind is wrapped in God, and tastes of the sweetness of eternal joy ” (Ladder, 10 & 2). In this state, the soul experiences a relationship with God which surpasses human words and cannot be contained by them: “Contemplation surpasses all the senses” (Ladder, 10). In much the same way, our Gregorian melodies regularly break out of the limitations of the words into the characteristic jubilus, that lyrical flow of pure wordless melody. In our example it is perfectly exemplified in the word amoris. Who better than St. Augustine has ever described that aspect of the chant and its affinity to contemplation?

“Sing to Him a new canticle: our whole longing yearns after it, singing the new canticle. Each one will ask how to sing to God. Lo and behold, He sets the tune for you Himself, so as to say: do not look for words, as if you could put into words the things that please God. Sing in jubilation. What does singing in jubilation signify? It is to realize that words cannot communicate the song of the heart. The jubilus is a melody which conveys that the heart is in travail over something it cannot bring forth in words. And to whom does that jubilation rightly ascend, if not to God the ineffable? Truly is He ineffable whom you cannot tell forth in speech; and if you cannot tell Him forth in speech, yet ought not to remain silent, what else can you do but jubilate? In this way the heart rejoices without words and the boundless expanse of rapture is not circumscribed by syllables. Sing well unto Him with jubilation.”

(2nd discourse on Ps 32)